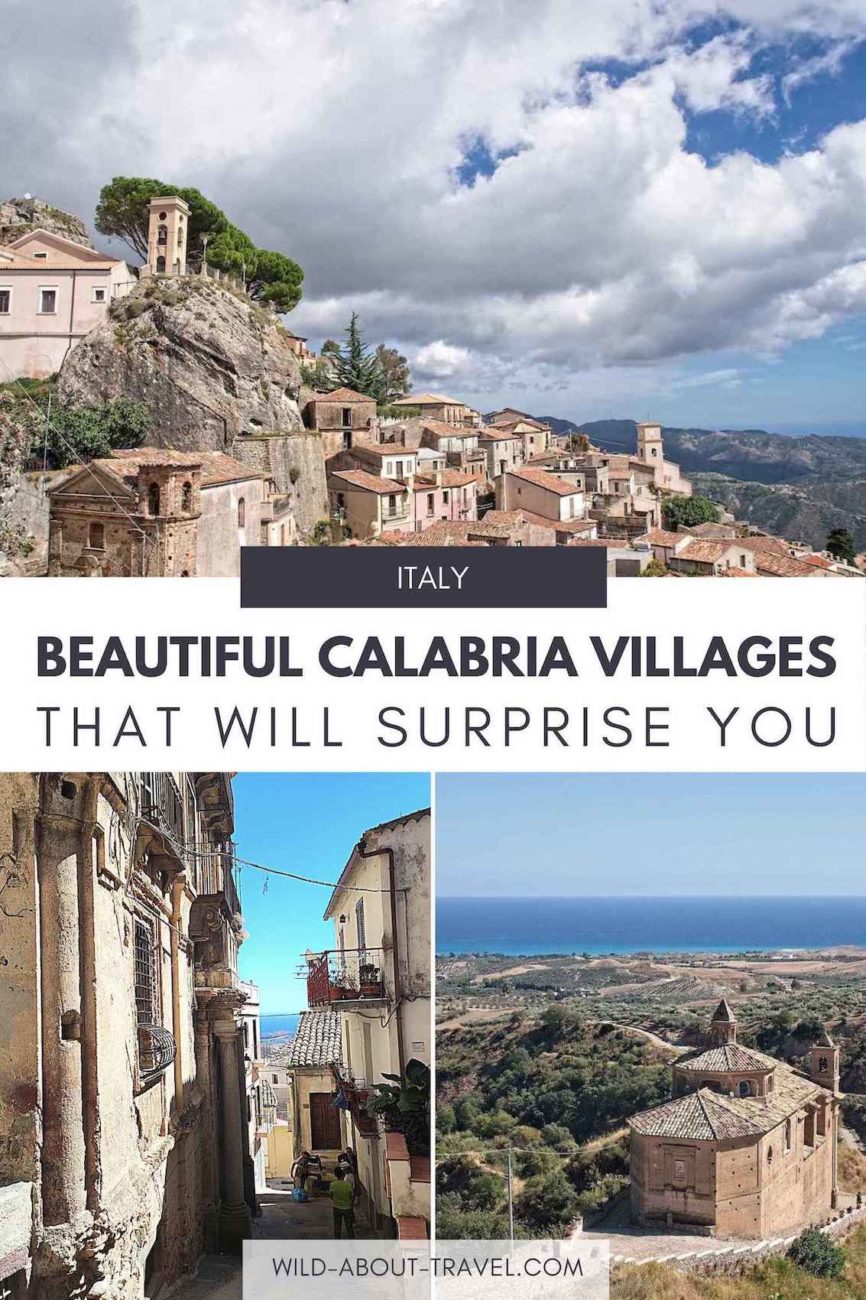

Do you want to discover little-known, beautiful Calabria villages? Travelling from north to south, I visited 9 towns in Calabria, and every one of them was a surprise.

Calabria is one of the most overlooked Italian regions and even those who visit usually spend time somewhere in a beach resort. After all, Calabria has an 800 km coastline and is one of the sunniest areas in Italy.

However, it’s inland that you’ll find many charming towns and the layers that history impressed throughout the centuries. Prehistoric sites, Greek heritage, Roman ruins, Norman castles and other testaments from the past. There are several reasons for that.

Calabria is mainly covered by hills and mountains; plains account for only 10 per cent of the region’s surface. Historically, after the coastal splendour in Greek and Roman times, the wars and repeated invasions from the Goths, Longobards, Byzantines, and Arabs drove the local residents inland. They built hilltop villages with a fortress at the highest point to dominate the plain, control the coast and block access to incursions from enemies.

Centuries later, things reversed. People increasingly moved from the townlets, often isolated and poorly connected, to the coast. In some villages, the depopulation has been so extreme that the hamlets have become ghost towns. Luckily, in several borghi – as villages and small towns are called in Italian – many residents, including young people, decided to revive their hometown. Driven by passion, they invest their time and work hard, often as volunteers, to enhance their heritage and promote it to visitors.

If you have visited Italy before, especially Italian must-see destinations, you’ll quickly discover that Calabria is a different world. This area has been scarred multiple times over the centuries, starting from a fragile environment. Devastating floods and earthquakes left their marks.

Isolation and scarce development – industrial and, to a certain extent, touristic – ironically make Calabria so unique. This is one of the Italian regions where you’re sure to have an authentic experience, especially in Calabria villages. In these hilltop towns, life has a different pace. Time flows slowly. Human relations and solidarity between the residents are palpable.

In restaurants, there are few chances of being presented with a multilanguage menu displaying some of the best-known Italian dishes, especially abroad. You’ll hardly find Carbonara or Lasagne. But you’ll discover a whole new world of local specialities, often made with locally-sourced ingredients and following traditional recipes handed down from one generation to another. Food in Calabria is a serious matter. It involves much more than just eating. It’s about sharing and hospitality.

Driving in Calabria, especially inland, is all about curvy roads climbing up and down hills and mountains. And more often than not, roads are in terrible shape. To visit Calabria villages, you must prepare for long drives to cover short distances. However, you’ll be rewarded with beautiful landscapes and picture-perfect hilltop villages appearing suddenly along the way.

My Calabria itinerary led me from north to south. I discovered charming villages, learned about the different cultural heritage across the region and breathed the unique atmosphere of travelling off the beaten path.

I spent 10 days in Calabria, but if you have a shorter time, you could focus on one of the main areas: north, centre and south.

Let me help you discover some of the most beautiful Calabria villages and unearth hidden gems in Italy.

Northern Calabria: Delightful hilltop towns in the Pollino National Park

The Pollino National Park is the largest in Italy and a UNESCO Geopark, spanning the Calabria and Basilicata regions. This vast area encompasses 56 villages, of which 32 towns are in Calabria, in the province of Cosenza. There, I visited three townlets, each of them with its own character and historical heritage.

Read also: Basilicata Region: A Journey To Discover Authentic Italy

Morano Calabro, the gem of the Pollino

I didn’t know it yet, but the drive from Lamezia Terme – where I picked up my little rented Panda car – on the Salerno-Reggio Calabria highway heading north was an introduction to driving in Calabria. The road is often curvy, climbs up and down the hills, and most of the time, speeding is not an option. Once I exited the freeway and approached Morano Calabro, I gasped in surprise. Suddenly, I saw a conic-shaped hill in front of me, with houses clinging to its slopes. The view was mesmerising, and I couldn’t help halting the car in an appropriate space and snapping a few photos.

Morano Calabro is one of the Borghi Più Belli d’Italia (Most Beautiful Villages in Italy) and has also been awarded the Orange Flag by the Italian Touring Club, a quality mark for small towns that embraced sustainable tourism development. As I strolled up the steep, winding alleyways, it didn’t take long to see why. I felt charmed by the old stone houses, their balconies or terraces decorated with green succulent plants, able to resist heat and long periods of drought.

Don’t expect Morano Calabro to be like some of the overpolished villages in other parts of Italy, beautiful but sometimes even too affected. Ornaments are generally unpretentious and spontaneous, conveying love, care, and great taste. At the end of September, there are only a handful of tourists, so you’ll primarily meet locals. Elderly people sitting on a bench and chatting, kids going to school or playing around, and shopkeepers on the threshold, speaking with residents.

The ruins of the Norman-Swabian castle at the top of the hill are one of Morano Calabro’s main attractions. Its origins date back to the Roman empire when it was likely a small fort or a watch tower. Then, during the Middle Ages, the Normans built a castle on the previous Roman foundations. Its present shape stems from 16th-century refurbishments due to the will of prince Pietro Antonio Sanseverino. From Morano Calabro castle ruins, you get spectacular 360-degree views, particularly beautiful at sunset.

The town’s other attractions are all related to religious buildings. Must-sees include the stunning Polittico Sanseverino, painted by the Venetian artist Bartolomeo Vivarini in 1477, St. Peter and Paul church and its exquisite Rococo interior, and Santa Maria Maddalena collegiate church, with its distinctive colourful tiled dome.

Morano Calabro is best discovered by strolling up and down the narrow meandering lanes. Lovely during the day, they become charming and romantic at night. The village is a perfect base to explore the Pollino National Park, better by hiking or biking. I had a day hike in the area where Calabria meets Basilicata and was impressed by how wild and beautiful this mountain area is. If you get the chance, make sure to see Heldreich’s pines, a superb family of pines growing only in a few places in Mediterranean Europe.

Papasidero, home to a unique prehistoric site

About 45 km from Morano Calabro, Papasiero is home to the Grotta del Romito (Romito Cave), one of the most important and oldest prehistoric sites in Italy and Europe. Incredibly, its discovery is very recent and dates back only to 1961. The unveiling gave an immediate start to research from Florence University, which determined that there was a human presence in this area since the Paleolithic era. The cave, located within a narrow canyon, offered protection and shelter, and its interior is superb. Archaeologists found several burial sites outside the cave and one of the most unique engravings: the image of an enormous bovine now extinct: the Bos Primigenius.

From the Romito Cave, the 13 km drive to Papasidero village is mostly twists and turns on a road whose conditions have seen better times. I had to focus on driving, but from the corner of my eyes, I could see how superb the surrounding scenery was. Thus, I made a few stops to admire the verdant hills and an almost untouched landscape. The view of the tiny hilltop town of Avena is delightful, as is the sight of Papasidero once approaching the village.

Papasidero, indeed, isn’t as pretty as other hamlets, but there are a couple of spots worth visiting. The main attraction is the Sanctuary of Nostra Signora di Costantinopoli. You rarely get to see a religious building leaning against a rock in an almost unreal setting.

Aside from and beyond its historical, cultural and natural appeal, Papasidero is the place to go if you’re passionate about active travel and adrenaline activities. Rafting on the river Lao is becoming increasingly popular thanks to the wild landscape and deep gorges.

Laino Borgo and Laino Castello: murals and a ghost town

One of the northernmost Calabria villages, at the border with the Basilicata region, Laino Borgo is immersed in the Pollino National Park.

Laino Borgo is a place rich in history and centuries-old traditions, surrounded by the rivers Lao and Iannello and by the luxuriant vegetation that adorns its banks.

The ongoing archaeological excavations indicate that the town’s origins might date back to the 6th century B.C. when ancient Laos was a prosperous colony of Magna Graecia. While these researches are still underway, there are sure signs of Byzantine and Longobard domination.

The town’s main historical attraction, a couple of kilometres away, is the Sacro Monte di Laino Borgo, generally known as Santuario delle Cappelle (Sanctuary of the Chapels) for its 16 chapels. The Sanctuary, also called Laino Borgo Little Jerusalem, was built in the mid-16th century by Domenico Longo and successively expanded. Longo, a devout from Laino, started the construction after a trip to the Holy Land. At that time, pilgrimages had become difficult and expensive. Longo thus decided to give people an idea of the main sacred places of Jerusalem through the chapel’s decorations.

What sets Laino Borgo apart are the murals scattered throughout the village. The most charming are the ones adorning the alleys close to the river, showing what used to be the traditional local life. Women harvesting, people chatting on a bench, families attending daily chores. I was reminded of my childhood when we used to sit all together to shell beans or cooking tomatoes in a giant cauldron to make preserves that would last for the rest of the year.

If you like active travel, there are many options around Laino Borgo. However, the most popular activity is rafting on the river Lao, in beautiful and uncontaminated scenery.

Sitting on top of a rock, the tiny hamlet of Laino Castello looks like a sentinel, watching Laino Borgo below. It was abandoned in the 1980s due to hydrogeologic and seismic threats and is not a ghost town. However, once a year, during the Christmas period, the village comes to life again with the Living Nativity scene. Locals re-enact the Nativity in the caves and the streets of the abandoned historic centre, and during the event, people can taste local food specialities.

Central Calabria and the province of Catanzaro

Catanzaro may be the smallest province in Calabria, but it offers a lot to see and do, from gorgeous beaches and crystal-clear water to delightful villages, not to speak about the beautiful mountain landscape of the Sila National Park. The Isthmus of Catanzaro, a narrow valley spanning the Tyrrhenian and the Ionian seas, is the narrowest point of the Italian peninsula. From some areas, on clear days, it’s possible to enjoy a sprawling view of the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Ionian Sea, the Aeolian Islands and even the top of Etna.

Squillace, a charming hilltop village

From northern Calabria, I headed southwards, towards the Ionian coast. My first port of call was Squillace, one of the most charming towns in Calabria, perched on a hilltop at 345m above sea level. While its origins date back to ancient Greece, Squillace also appears shrouded in mystery and legends. The village’s foundation is sometimes attributed to no less than Ulysses. Others ascribed the creation of Squillace to Menesteo when he returned from the Trojan war.

Like many other Calabria villages, Squillace’s development during the Middle Ages is linked to defensive purposes. The town held a strategic position overlooking the gulf and was coveted by the Saracens, the Arabs and, later, the Normans. People moved inland, on the hills, to escape and control incursions from the sea. There’s no medieval village without a castle, and Squillace has its own, towering at the village’s highest point.

The ruins of the ancient fortress, severely damaged by the violent 1783 earthquake, have been lovingly restored, and one can easily imagine how imposing the castle was. As this was not enough, you’ll be rewarded with sweeping views after the climb, spreading from the mountains to the cobalt-blue Ionian sea.

Earthquakes didn’t spare the cathedral either. While its first construction dates back to the 11th century, the present building was erected in 1798. The facade, inspired by the Romanesque style, is imposing in its simplicity. While the interior is not particularly remarkable, the cathedral square is the liveliest spot, where you can watch the local people in their day-to-day life.

It’s, however, a few steps from the cathedral that I saw what ended up being my favourite attraction in Squillace: the suggestive ruins of Santa Chiara church and monastery. Dating back to the 17th century, Santa Chiara didn’t escape the devastating effects of the 1783 earthquake. Still, the ruins hinted at its past splendour and sparked a strong emotion in me.

Talking about religious buildings, don’t miss Santa Maria della Pietà, a small church concealed in a narrow lane. With its simple gothic structure, it’s a treat. Regrettably, I couldn’t see it inside and admire the ancient cross-vaulted ceilings.

If you like pottery, you’ll be pleased to see the many artisan shops, mainly on Corso Pepe and in the area near the castle, continuing a cultural heritage getting as far back as Ancient Greece.

Like many other borghi (small towns) in Italy, there’s no better way to discover and appreciate Squillace than slowly wandering in its charming alleys, admiring the stone doorways of the once noble palaces and the delightful courtyards. Squillace is also its people: the nonnas standing or sitting in front of their home’s door, waiting for someone with whom having a chat, the kids coming back from school, and the locals greeting one another in the streets.

Roccelletta di Borgia and its unique Archaeological Park

While the inland town of Borgia admittedly is of limited interest, except for the cathedral and a few other buildings, the actual attraction is Rocelletta di Borgia. Overlooking the Ionian sea, Roccelletta di Borgia is home to the Scolacium Archaeological Park.

Although not far from Borgia, it took me some time to reach the archaeological site since signs in this area are often confusing. But I’m stubborn, so in the end, I got there! And it was worth the effort.

If you visited Rome, you certainly got an idea of the legacy of ancient Greece and the Roman empire on Italian culture and art. Even the highly admired works of the Renaissance couldn’t have existed without the Greek and Roman cultural heritage. The archaeological finds in Scolacium may not be as eye-catching as other Italian landmarks, but they’re undoubtedly worth a visit. Additionally, they are the most important Roman ruins in Calabria.

First of all, the setting is somewhat unusual and charming. The Roman ruins are set amid an old olive grove, and thanks to the slight elevation, some of them stand out on a palette whose colours range from the yellow of the dried fields to the silver-green of the olive trees to the deep blue of the sea. I reckon that Scolacium gets busier in the peak season, but the atmosphere was absolute magic on a September weekday with only a handful of visitors.

Start your visit with the small but insightful Museum. You’ll get an introduction to the site’s history and find out that although the ruins date back to the Roman age, it had previously been a Greek colony named Skylletion. Furthermore, you’ll learn about the excavations after the site discovery in 1982 and admire some of the findings. After that, you’ll be ready to slowly wander among the olive groves to visit the archaeological remains.

While all of Scolacium Archaeological Park is interesting, two ruins impressed me the most. One of them was the well-preserved Roman theatre. Built on the natural slope of the hill, it could host up to 3500 spectators. The other was the amphitheatre, a little further up. Although there’s not much left of the original structure, the setting is beautiful. The ruins, gently laid against the slope like a blanket, and the deep blue of the sea on the horizon rendered this spot mesmerising.

And then there’s the imposing Basilica of Santa Maria della Roccella. Built in the 11th century by the Normans, historians believe it to have been the largest religious building in Calabria. The monumental ruins are impressive, and looking at its Romanesque structure in red bricks, it’s easy to imagine what a gorgeous building it must have been. I felt so fascinated that I couldn’t resist snapping photos and having my camera in full swing.

Badolato, a delightful medieval town

As I drove yet another winding road, Badolato appeared like a fairy-tale village perched atop a rather steep hill. I halted the car at the first suitable spot, grabbed my camera, and climbed down to take a few photos. Unfortunately, the town was backlit, but it was impressive all the same.

Badolato is a charming medieval borgo (the Italian name for a small town) that is deep-rooted in history and one of the most beautiful towns in Calabria. It was the Norman adventurer Robert Guiscard – famous for his conquest of southern Italy and Sicily – who commissioned the building of the hilltop castle in 1080.

Over the centuries, due to its strategic position overlooking the sea and allowing it to watch for possible raids from enemies, Badolato ended up under successive rulers’ control, craving such a key location. Like many other villages in the area, Badolato endured the horrible 1783 earthquake, which spread extensive destruction and killed about 5,000 people. Although deeply scarred, the hamlet kept its typical medieval structure, with the crisscrossing meandering lanes.

In the 1980s, Badolato experienced the same fate as many other Italian townlets: depopulation. The risks that it might become yet another ghost town were real, and a brilliant initiative was launched: Badolato was put on sale. The opportunity met with maybe unexpected success. Several people, above all from northern Europe, invested in the houses and renovated them. Therefore, don’t be surprised if you meet “locals” speaking German or other foreign languages.

One of Badolato’s main characteristics is its churches. That might not come as a surprise in a country like Italy, where churches are ubiquitous. Still, 14 religious buildings in a hamlet of about 3,000 residents is a lot! Even if you’re not a worshipper (and I’m not), churches are often worth visiting, if only for their architecture and the artistic masterpieces they usually house. My favourite was the church of Immacolata (Chiesa dell’Immacolata), dating back to the 17th century and sitting on a panoramic terrace overlooking the gentle hills and the azure blue of the Ionian sea. Sadly, I couldn’t visit the interior since it was closed when I was there. I always forget that churches have opening hours.

Badolato is a town best discovered at a slow pace, getting lost in the meandering alleys and enjoying the atmosphere that feels like stepping back in time. At the end of September, I was surprised to find a sleepy hamlet with no more than a handful of people. While I’m not too fond of the crowds, I would have expected more people to visit such a charming borgo. But it was also lovely to have the village almost all for myself.

Southern Calabria and the Greek Heritage

No region in Italy has preserved the Ancient Greek heritage like southern Calabria and the area of the Reggio Calabria province.

After 500 years of Greek domination, in the 2nd century B.C., the Romans became the new rulers, followed over the centuries by the Byzantines, Normans, and Bourbons, to mention only a few. Despite the whirlwind of cultures, the Greek heritage survived in traditions and language.

Over time, a fascinating phenomenon occurred. The contamination between ancient Greek and local dialects gave birth to a new language: Grecanico. Sadly, after having survived for centuries, Grecanico is being increasingly abandoned. But there are still people speaking it and trying to preserve such a unique legacy.

Bova Superiore, one of the most beautiful Calabria villages

Considered the heart of Calabria’s Grecanica area, Bova Superiore (beware not to confuse it with Bova Marina, by the sea) is a delightful hilltop village in the Aspromonte National Park. Although only 9km from the coast, the hamlet is at an altitude of 820m above sea level. Thus, the drive is quite a climb.

Arriving in Bova’s main square, you’ll be welcomed by the beautiful 740 Ansaldo Breda locomotive from 1911, standing as a symbol of Italian emigration worldwide. Then, as you move your first steps, the first things that will grab your attention are the streets and shop signs in Italian and Greek.

Because of Bova’s rather unique traits, I suggest you visit the Museum of the Greek-Calabrian language “Gerhard Rohlfs” before you even discover this beautiful town. Opened in 2016, the Museum is dedicated to the German linguist and his lifelong studies of the Greek-Calabrian language and culture, shedding light on the heritage of this area.

A kind local girl offered to guide me and explained the importance of Rohlfs’ work while highlighting the main exhibits. At first, I was skeptical that such a Museum might be exciting. After only a few minutes, I proved wrong because there were plenty of photos, objects, and tools showing the life and traditions of Greek Calabria. Old pictures of traditional costumes, beautiful textiles that showed the incredible skills of Calabrian women, and lots more.

Bova is one of the Borghi più Belli d’Italia (most beautiful villages in Italy); additionally, the town was awarded the Orange Flag by the Touring Club Italiano, a recognition given to small towns active in quality and sustainable tourism. The borgo is genuinely charming and lovingly kept by its 400 residents. Compared to other villages that come to life only during the tourism season, Bova is lively all year long as the locals enjoy spending as much time as possible in their hamlet.

On the hilltop, you’ll see the ruins of the 11th-century fortress. It was built by the Normans, who chose the spot due to its strategic position, dominating a vast area. The sweeping vista from the castle is breathtaking. The mountains of Aspromonte at the back, the rolling hills at the front, and the Ionian sea, blue like a sparkling sapphire, further away.

Walking down the winding alleyways, I visited the ghetto, where a small Jewish community lived between the end of the 15th and early 16th centuries. The Giudecca – another name for the ghetto and a word that may sound familiar if you visited Venice – has been lovingly restored and decorated with beautiful ceramics created by a talented Calabrian artist, Antonio Pujia Veneziano.

Descending further along the meandering streets, I halted every few steps to admire the cathedral, the elegant Palazzo Mesiani and a few other aristocratic buildings. Back to the main square, I strolled to the gorgeous Palazzo dei Nesci Sant’Agata, with its crenellated arch, built in 1822.

In a nearby alleyway, I followed the signs to the Sentiero della Civiltà Contadina (the Path of Peasant Civilization). It’s a lovely open-air museum showing ancient working tools in a delightful setting. With all the modern machinery, we have forgotten how hard the peasants’ life was, and the path is an excellent testament to the old farmers’ culture.

You can track down traces of the Greek legacy also in the local food. Restaurants’ menus combine typical southern Calabria dishes with delicious Greek recipes. One of the most popular joints serves lestopitta, a crunchy flatbread filled with ingredients of your choice: cheese, vegetables, or cured meat, all strictly local.

Bova is such a quaint hilltop village that you should spend at least one night to savour its unique atmosphere. After sunset, the hamlet glows under a warm and magical orange hue. And at sunrise, the vista of the rolling hills and the coast is breathtaking. Of all the towns in Calabria I visited, Bova Superiore was my favorite.

Pentedattilo, the picture-perfect hamlet

Set against the cliffs of Monte Calvario in a picture-perfect setting, Pentedattilo is a magical village. Its name derives from the Greek pènta-dàktylos, meaning five fingers, and stems from the shape of the backdrop cliffs, resembling a gigantic hand.

Although only 250m above sea level, the scenery is such that it feels much higher and makes you think of the mountains way more than the sea. The landscape is mesmerising: rugged mountains, rolling hills, green fields and the deep blue sea. Add to this the many pickle pears plants, and you’ll get one of Calabria’s most typical – and beautiful – landscapes.

Like many other isolated villages, residents progressively abandoned Pentedattilo, which in the 1960s, became a ghost town. Luckily, from the 1980s onwards, a few volunteers from all over Europe decided to get back to the hamlet. Some of the houses have been restored, and a few artisan shops opened, but residents are still only a handful.

I was greeted by a group of cats – the true rulers of the hamlet – enjoying the sun in front of a charming artisan shop. Giorgio, the shopkeeper and one of the few residents, came to me for a chat, which must be a treat in such an isolated hamlet. “Life is not easy in Pentedattilo”, he told me, “as there are not many modern amenities”. Still, difficulties don’t deter him and his determination to stay. And thanks to him and the few other residents, the village remains alive.

Pentedattilo is one of those hamlets that needs to discover slowly, savouring it like a god’s nectar. Step after step, as I climbed up the tiny winding alleyways, I looked at the refurbished stone houses embellished with simple but charming decorations. I stopped by the bench of kisses, overlooking the rolling hills and the sea, offering a spectacular backdrop for a photo. Further uphill, I could admire St. Peter and Paul church’s facade, which, luckily, survived the 1783 earthquake.

Shortly after, I got to the castle ruins, sitting on a rock at the top of the village. During the Romans, a fortress towered above the town, strategically placed to check on possible enemy incursions. Centuries later, at the end of the 16th century, the Alberti family, which controlled the hamlet, converted the fortress into a castle. Most of the building is ruined out, but at the end of the climb, I was rewarded with a magnificent vista.

As I got ready to leave, I gave a last glance at this magical town. I left it behind, nurturing the hope that it won’t be abandoned once again.

Roghudi Vecchio, a rough drive in a wild landscape

At an altitude of about 530m above sea level, in the Aspromonte National Park, Roghudi Vecchio – not to be mistaken with Roghudi (Nuovo) – is a rather peculiar ghost town.

The village sits on a steep rock, isolated, in an area where hydrogeological calamities are frequent. Two terrible floodings in 1971 and 1973 left widespread destruction and death. The local authorities ordered the residents to evacuate the hamlet, which became a ghost town.

To reach Roghudi Vecchio, you must get ready for a rough drive. There are two ways to get there: from Bova or Melito Porto Salvo, and the road conditions range from very bad to godawful. I drove both of them, and although highly scenic, I strongly advise against the ride from Melito Porto Salvo unless you have a sturdy 4×4.

While the hamlet is not particularly attractive, it’s worth visiting for the sweeping views of a wild and marvellous landscape. Perched on a steep spur overlooking the dried bed of the Amendolea River and the rugged Aspromonte mountains, Roghudi Vecchio felt out of this world. Completely alone – except for a few goats – I walked in the narrow lanes between the now crumbling houses, glancing inside to spot the few signs of life left. The only building slightly refurbished is the tiny church of San Nicola, where the filtering lights create a unique atmosphere.

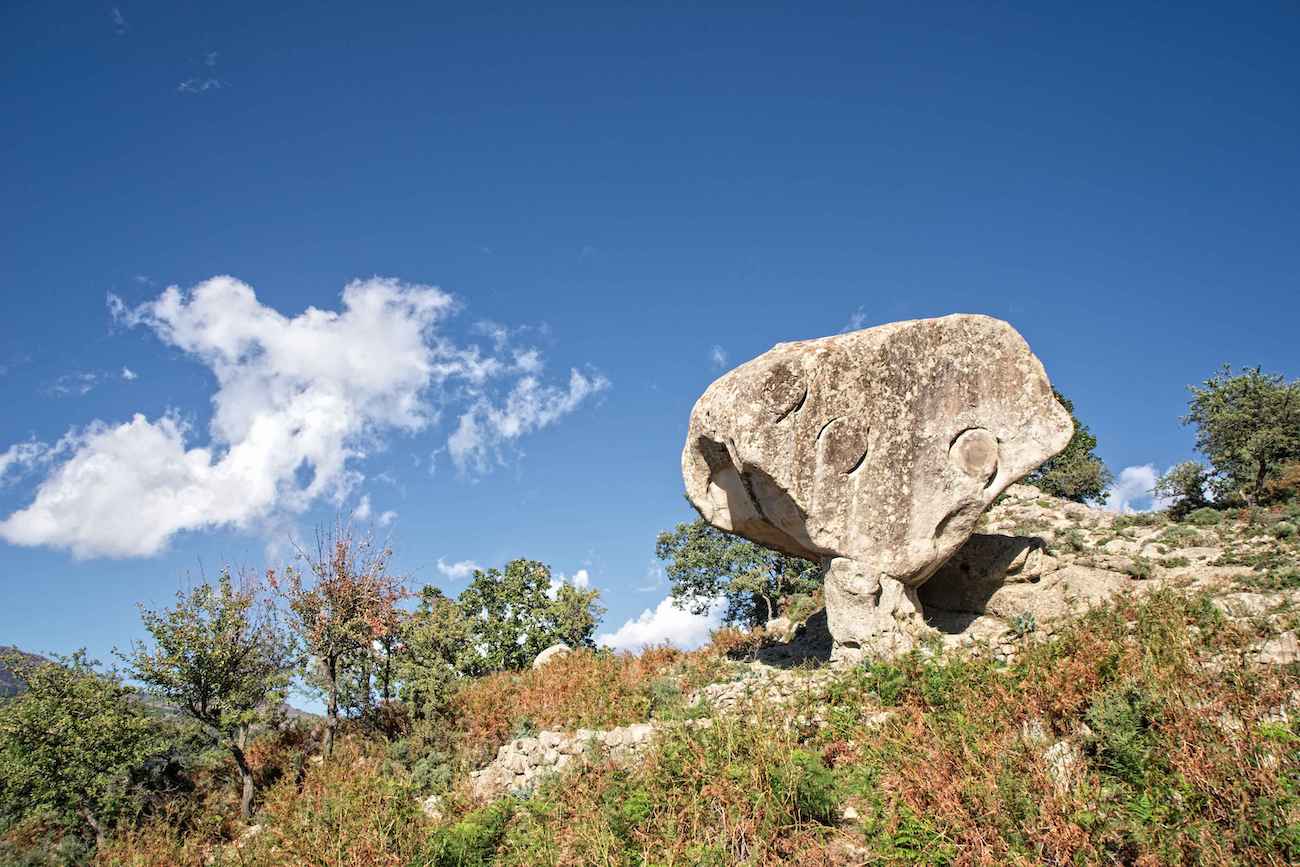

On the way to Bova, some 5km from Roghudi Vecchio, I took a break to visit Rocca del Drako, a unique Geosite surrounded by the wild scenery of the Aspromonte National Park. A short, easy walk led me to Draco’s Rock, a natural sculpture shrouded in mystery. Its shape evokes a squared head, and the two circles carved in the middle suggest eyes. Thus, unsurprisingly, the rock served as an inspiration to many legends. One myth tells that it was home to a dragon protecting a treasure. To those yearning to possess the precious goods, the dragon asked for a sacrifice: a black cat, a goat and a child, all males. Useless to say that no one ever found the treasure.

The Geosite also hosts another natural sculpture called Caldaie del Latte (Milk Boilers). The seven small boulders also inspired a legend linked to the dragon, said to devour children and provoke calamities. To satiate and mollify him, the locals would boil milk in gigantic cauldrons to feed the terrifying monster.

Legends apart, Rocca del Drako is a beautiful site worth a visit.

Calabria Villages: Practical Info

Best Time to Visit Calabria

Calabria is one of the Italian regions with the highest number of sunny days and is, therefore, a year-round destination.

However, summer can be scorching, while in Spring and Autumn, the mild temperatures are more enjoyable. Additionally, the shoulder season is perfect for beating the crowds, although some villages may have limited options in terms of accommodations and food. Winters are mild in central and southern Calabria, but beware of possible snow in the mountains. While the white-blanketed hamlets are undoubtedly charming, the often poor road conditions might pose some challenges.

How to Get to Calabria

There are two airports in Calabria: Lamezia Terme and Reggio Calabria. Since this Calabria itinerary covers the region from north to south, you can get in at one of the airports and out from the other.

You can also get to Calabria by high-speed train, which stops in Paola, Lamezia Terme, Villa S. Giovanni, and Reggio Calabria.

How to Get Around

You’ll have to hire a car to visit the Calabria villages since public transport is minimal. I’m usually a big fan of small, simple cars. However, more than once, I wish I had rented a 4×4 to climb up and down the steep hills, often on dismal roads.

_______

This article was written in collaboration with iambassador for the ‘Viaggio Italiano’ Project (Italian National Tourist Board, Ministry of Tourism & Conference of Regions and Autonomous Provinces)

Pin for later!